Original Article by:

Irene Zugasti Hervás

Translated by: WCCC Toronto

****

This piece is translated from a 2016 article in the Basque Feminist zine, Pikara Magazine. Images and report made during the Humanitarian Caravan to Donbass in May 2015.

***

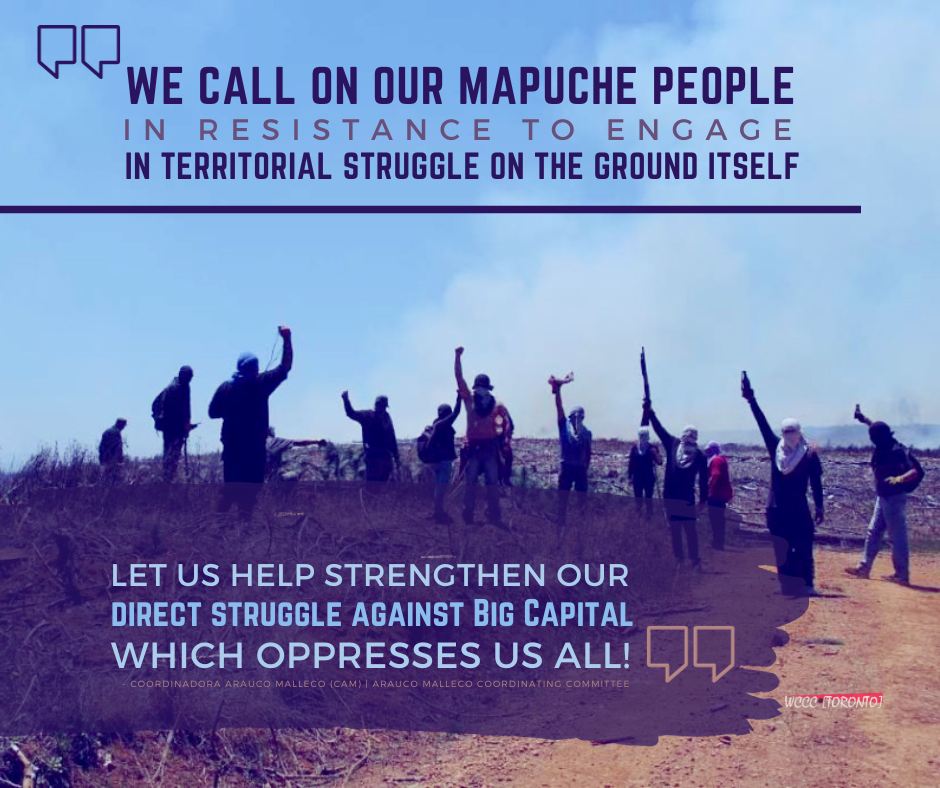

The images of beautiful activists wrapped in national flags in the Maidan square or those of old women crying have given a reduced and stereotyped vision of the role of women in this conflict. The female population is active in all war structures, including popular militias.

Walking through Alchevsk, in the self-proclaimed Lugansk People’s Republic in eastern Ukraine, inspires more uneasiness when thinking about its future than its recent past. It is a small industrial city, embraced by a huge steel mill that frames the horizon with huge chimneys. The heavy industry, so symbolic of the region’s Soviet past, was paradoxically its lung, until the war broke its glass windows.

Elderly local women, their flower-embroidered scarves tied around their necks, line up at the militia’s makeshift soup kitchen in a dilapidated building. They are the majority in that city of silence, which is part of the Donbass region controlled by the militias with broad popular support and which has unfairly been called dryly pro-Russian, with the aim of making this war, like all wars, a conflict in black and white, burying all shades of grey. They carry their lunch boxes in cloth bags and crawl back through the deserted avenues, step by step. Pension money hasn’t arrived in Alchevsk since last summer. With the massive exile of the youth, the enlistment and alcoholism wreaking havoc on the population, they, the retired, the poor, are the worst off in this war.

The civil war in eastern Ukraine is undoubtedly one of the most unfairly treated conflicts in the circus of international relations: manipulated by obscure geopolitical interests, scorned by the media and without official channels for humanitarian aid, the war in Donbass continues to claim death and silence.

Cynthia Enloe, a pioneering academic in making her way in International Relations from feminism, wondered twenty years ago where women were when talking about diplomacy, war, and the State. Since then, an exciting school has been built around that question.

“The civil war in eastern Ukraine is undoubtedly one of the most unfairly treated conflicts in the circus of international relations: manipulated by obscure geopolitical interests, scorned by the media and without official channels for humanitarian aid, the war in Donbass continues to claim death and silence.”

Where are the women in Ukraine? If Enloe raised that question today, women from Donbass would probably not be among the answers. Female visibility in this conflict has been limited to the images of beautiful activists wrapped in Ukrainian national flags in the Maidan square, which—in the purest style of the Slavic normative femininity stereotype—is very attractive for the international sex market. Blondes with enormous blue eyes, young, cold—icons of the desire for modernity that has worked so well in the propaganda of the Ukrainian activist franchise in depicting the feminine as vectors of liberation, although it is not known exactly what they are liberating themselves from. The other most recurrent image if we think of Ukraine has been that of the victimized women, the weeping old women, those mutilated by the bombings, suffering the pain of the war in their flesh, crawling in silence between the destroyed houses.

Carol Cohn said in her impeccable book Women and Wars that one had to know how to flee from the dichotomy of victims and executioners (a highly sexualized duality) if one wants to approach a warlike conflict. The woman is peace, the domestic, the raped, the protected, the warrior’s rest; the man is the protector, the belligerent, the owner of public space, the lord in all wars. The rancid refrain of “women, children and the elderly” to refer to the human cost of a war is as hackneyed as it is false.

“Where are the women in Ukraine? If Enloe raised that question today, women from Donbass would probably not be among the answers. Female visibility in this conflict has been limited to the images of beautiful activists wrapped in Ukrainian national flags in the Maidan square, which—in the purest style of the Slavic normative femininity stereotype—is very attractive for the international sex market. “

Unlike other contemporary wars that occupy front pages, on the side of Donbass—depicted on television news as pro-Russian, separatist and insurgent—corpses here are not mourned. Its enemy is the Ukrainian army, which obeys a government installed with western sponsorship (the so-called Kiev Junta), a presumed champion of democratic values, despite having the extreme right widely represented in its ranks through movements such as the Right Sector or Svoboda.

The Kiev army is shrouded in unknowns: from forced mobilizations to desertions of young people fleeing the massacre in the East, little is known about the actual functioning of a recently restructured army, formed especially for this war and in which some of its cadres were hooligans and members of far-right paramilitary guerrillas.

“It would be unfair to deny that on this side of the trench there are also different currents and interests, but the strength of the social, political and cultural project that is being built around these People’s Republics is not mere propaganda. It is a force that is felt as soon as you set foot in Alchevsk, in Kirovsk, in Stakhanov, in Krasnodon.“

The popular militias of Donbass organized themselves at the beginning of the war in 2014 to defend their territories from what they consider imperialist aggression to impose the domination of Kiev. Today, these militias control large regions within the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics. It would be unfair to deny that on this side of the trench there are also different currents and interests, but the strength of the social, political and cultural project that is being built around these People’s Republics is not mere propaganda. It is a force that is felt as soon as you set foot in Alchevsk, in Kirovsk, in Stakhanov, in Krasnodon.

The People’s Republics (RP), which today are going through a complex process of development, lay foundations in their socialist heritage, times when the region enjoyed its golden age. These new state-building projects would never have borne fruit without the strength and development of the popular militias from the beginning of the war, which were the engine for the collective awakening. Parallel to their military development, the RP have woven political and cultural networks, but also economic ones with projects for the nationalization of natural resources and self-management and cooperativism in industry and local agriculture, always stalked by the voracious threat of the local oligarchy.

Back to Enloe, then. Where are the women in Donbass? They are active in all war structures. From the beginning of the conflict, many joined the militias, both in combat and in the complicated bureaucratic network that surrounds them. There has been no problem freely enlisting in the popular militia, although some complain about the cost of reaching the front line. When you travel through the region you can see them: they are at checkpoints, in barracks and offices, walking among civilians, walking with tracking dogs and patrolling the streets.

“The People’s Republics (RP), which today are going through a complex process of development, lay foundations in their socialist heritage, times when the region enjoyed its golden age.“

The militia women who have joined the brigades range from very different ages and experiences, but their voluntary enlistment, when asked, responds to a common cause: to fight the government that massacres their people. Experiences have been generated as exclusively female battalions. In Krasny Luch, in the Lugansk region, 25 women, from university students to retirees and miners, began by forming barricades in the streets to end up forming a battalion that was later joined by the men of the town. The Rus battalion, formed in late 2014 and made up entirely of women, is another example. A local celebrity is Captain Nut, who is in command of a 50-man artillery unit in Donetsk’s Oplot Battalion, after quitting her job as a casino clerk. She would have died just the same by staying at home, so Nut learned to handle heavy artillery and was promoted in the strict hierarchy of these formations until she had fifty soldiers under her charge.

A few months earlier, Anna Aseyeva, press officer of the Phantom brigade, was killed in an ambush along with Commander Alexei Mozgovoy, who were inseparable in their work. The Ghost Brigade or Prizrak, a large-scale militia that controls part of the Lugansk region, takes its name from the fact that it is often left for dead, however, a new detachment always appears in the region. This brigade is the soul of the militia and has generated an organization whose networks go far beyond the military and are inserted into the daily life of many cities. Perhaps for this reason, the posthumous recognition of Anna was unanimous: those who knew the day-to-day of this war knew that her work was essential, or everything essential that a single person can be in the middle of a war.

The day to day in a war is not like the movies tell it. There are eternal shifts at the surveillance posts; whole days driving up and down empty roads, daily tasks carried out with boredom and hours that pass slowly, very slowly, waiting. They have to share guard posts and night patrols with a male majority; also lounge chairs, showers, daily chores. This is an experience that is not alien to the women of the place: In a militarized society like the former Soviet, militarization is transferred to all areas of life. At school, the girls and boys of the state school celebrate the day of Victory against fascism, on May 9, simulating war games with toy tanks and singing military hymns. They know how to dance and march in small formations, they dress in uniform and place flowers on the pyres of the unknown soldier and parade through the streets with military discipline. The history of their people is the cause of their present, and they are aware of it.

In the central park of the city of Stajhanov a golden statue of an industrial worker, with overalls and tools, stands in a small square. Another metallurgical worker carved in stone, together with her partner, received visitors at the entrance of the steel factory in the city of Alchevsk. The women of Soviet socialism championed the most worthy struggles and social conquests, often hand in hand, and many others face to face, against their own companions.

“From the image of the female-identified comrade of socialism—with all its limitations—women’s representation in post-Soviet society has degraded back to the family figure, raising children, as well as the cult of beauty and fragility in a country of oligarchs and princesses with long braids. “

In the military they were pioneers: a million women fought in World War II, such as the famous Night Witch aviators, the deadly snipers who became local celebrities or the lesser-known Russian artillery women. The USSR was in fact the first country in which abortion was made legal and accessible to all. It seems that modern feminism has forgotten that. From the image of the female-identified comrade of socialism—with all its limitations—women’s representation in post-Soviet society has degraded back to the family figure, raising children, as well as the cult of beauty and fragility in a country of oligarchs and princesses with long braids. This is in parallel to the massive entry of the sex and pornography market, persecuted (at least publicly) during the USSR, in a process that Attwood calls the re-masculinization of Russian society. Slavic societies have deeply patriarchal structures, seeing the resurgence of the conservative scourge of the Orthodox Church, which has intensified even more in recent decades. These consequences rippled from the political and economic crisis that Perestroika meant especially for women, who were ordered by institutions to return to their homes and leave their jobs. The West has pointed to this patriarchy to justify Russian aversion as an ever looming threat in geopolitics, but which has many parallels with the one that any Western society can experience.

“Complaints have also been reported by international journalists about the rapes and torture of women committed by the Azov Battalion – a volunteer detachment of the extreme right – in the military prisons of this unit, which reports directly to the Kiev Government.“

This perception of women’s issues as domestic and secondary in something as public and exposed as war leads to terribly understated issues such as sexual violence and women’s health in wartime. In the context of Donbass, there has been speculation with reports of rapes and disappearances of women in the territories at war that few want to engage with and about which little or nothing is known. The Government of Donetsk, the other popular republic in the region, declared having found the bodies of dozens of women raped and murdered by the Ukrainian army, information that neither the OSCE nor Human Rights Watch confirms or denies after a year. Complaints have also been reported by international journalists about the rapes and torture of women committed by the Azov Battalion – a volunteer detachment of the extreme right – in the military prisons of this unit, which reports directly to the Kiev Government.

But a war is a before, during, and above all, an after. As in Yugoslavia, as in Afghanistan, these crimes will only have some relevance years later, when the post-conflict period uncovers the reality of humanitarian devastation and the long-term consequences of a war that women always suffer to a greater degree. Let’s not forget that it is leaving thousands of refugees, displaced and exiled women who are not being talked about. The invisible weight of women in post-war periods and the work of disarmament, demobilization and reintegration will undoubtedly play a crucial role in this and other current hybrid conflicts.

“Listening to them, reading them, seeing them, is approaching a war with a gender perspective, undoubtedly opening new approaches and interpretations that not only break with the male hegemonic scheme, but above all, with the version of the news.”

But until this happens in Donbass, where tense calm continues to be the norm, the tasks the voice of women activists in Donbass has a special power: sites circulate on the network whose information has made them become references, the pages to which thousands of people come to get data different from those of the hegemonic version. Most of these blogs and information pages belong to women living in conflict zones who take the risks of writing for the world. Denya aka Little Hiroshima has become hugely famous with her blog about Lugansk. She was a Philosophy teacher in Moscow and an amateur traveler until she decided to become a volunteer in Donbass, rented a van and went there loaded with food. But she is not alone: there are poets, politicians, humanitarian activists, journalists. Listening to them, reading them, seeing them, is approaching a war with a gender perspective, undoubtedly opening new approaches and interpretations that not only break with the male hegemonic scheme, but above all, with the version of the news.

In these hybrid wars, the wars of postmodernity, with new actresses and actors, new scenarios immerge but with the recycling of old discourses and enemies with old echoes. Women’s participation in these wars has forced us to reconsider identities and spaces—such as in Kurdistan—because they are the active agents who have traditionally been excluded from the discourse of war, or worse, instrumentalized to show only the female face of the conflict in terms that favor male normativity.

Today, after a year and a half of the terrible summer of the siege of Lugansk, and living its second “winter of hunger,” the figures of the conflict that are handled speak of 9,100 people dead since the victims began to be counted in April 2014. More than one million people have been displaced in Russia and the same in Europe. Specifically in the last six months, in which the region has remained under the alleged ceasefire as a result of the Minsk II agreements, 575 civilian victims have been registered in the conflict zone, with 165 killed, most by mortars, cannons, howitzers, tanks. No one remembers that downed plane, the MH17. The Minsk pacts are actually dead paper. The humanitarian corridor remains unopened. Today, there is another enemy, far from Donbass, on the news.

Meanwhile, in the small town of Alchevsk, they are trying to restart the steel mill. Walk carefully in the snow-covered minefields. The neighboring city of Kirovsk is also trying to pull itself together: the teacher of one of her elementary schools comes over when she sees us taking photos. He says that thousands of people (20,000, out of a population of 25,000 inhabitants) had left far from there in just one year. In his class they ask him every day if the war is over because they don’t want to run back to the basement when they hear the bombs falling. And she asks us, with an anxious gesture. What do the news in your country say? Will the war end? In Kirovsk they don’t want money, medicine, or shelter. They just want answers. We prefer to look at the ground rather than tell her that nobody says anything about her and her future in our country.

She was a tall, smiling and brave woman who waved us off from the window with the promise of seeing each other again. She stood there, in the middle of the street, in Kirovsk, Lugansk People’s Republic, land of oblivion and silence, waving her arm, watching us go. The next day, she would go back to school.